Look up! This always counts as an invitation to enjoy and be amazed by the charm of the remote and unknown. However, it should also come as a warning sign to detect a lack in our eyes as we look beyond our usual sight. The lack of stars. Sometimes, having ‘the head in the clouds’ may come as an eye-opener on the problem of light pollution, but also on its possible solutions.

Since 1988, the IDA has been targeting some of those. Behind sentences such as “save the dark” and “protect the night” lies the mission of the International Dark-Sky Association (IDA), the recognised authority on light pollution. By providing “leadership, tools, and resources” as well as “access to information about the destructive impact of over-lighting” to individuals, policymakers and industry, the IDA aims to promote responsible and functional outdoor lighting that helps reduce light pollution. This is how, in 2020, the South Pacific island of Niue was officially recognised as the world’s first ‘Dark Sky Country’ “for its commitment to keeping light pollution to a minimum”. A rather small reality that, some might venture to think, should not have had much difficulty achieving the status.

Well, New Zealand is next, in an effort led by the Indigenous Māori people. Actually, it is first in line to become the biggest ‘Dark Sky Country’ recognized by the IDA. New Zealand can already claim 74% either pristine or degraded only near the horizon night skies on the North Island, and 93% on the South Island. Yet, the country is still expected to implement efforts over at least three years that should include “raising awareness, changing and implementing local light ordinances, and expanding protected areas”.

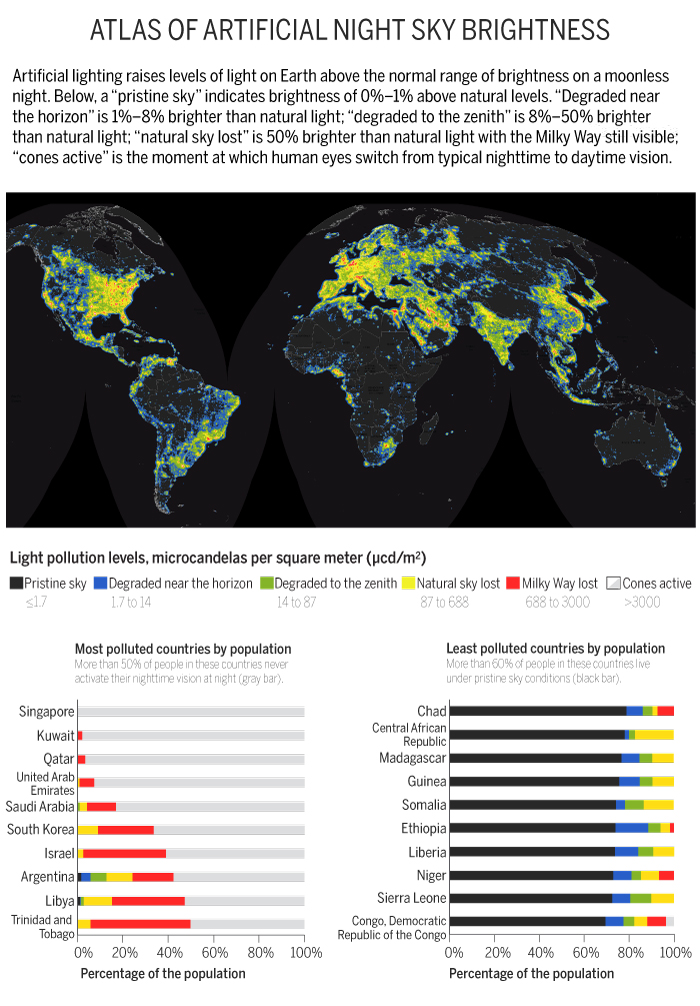

While an estimated 56% of New Zealand’s population cannot admire the Milky Way, more than 99% of European citizens live with light-polluted night skies. Data that is not hard to believe if one looks at the first light pollution atlas compiled by Fabio Falchi, an Italian researcher at the Light Pollution Science and Technology Institute (ISTIL), and his collaborators in 2001, by means of a U.S. Air Force satellite. “A useful communication tool”, Conservation Scientist Travis Longcore called it, “to open everybody’s eyes” and, along with the IDA, to offer fertile ground for solutions and key regulatory interventions.

The first step to counter the problem is understanding and recognising that a state of “permanent twilight”, such as the one presented by the atlas, hinders the human and poetic solace of stargazing and, more seriously, deteriorates melatonin production in humans as well as the thriving of biodiversity. In fact, according to Pere Horts, “the biological activity of our fauna [and flora] is more intense at night than during the day” and that’s why our natural ecosystems “need the night for their normal activities”. Specifically, “Strong artificial lighting at night” can turn bird migratory paths into death traps, “deter nighttime pollinators like bats,” and “disrupt underwater ecosystems”, not to mention worsen smog. The United Nations reported that in 2020 some countries “endorsed guidelines on light pollution covering marine turtles, seabirds, and migratory shorebirds” aiming to “call for Environmental Impact Assessments to be conducted for projects that could result in light pollution”. This means that the problem has started to be addressed and significantly recognised as a threat to mitigate.

“E quindi uscimmo a riveder le stelle“, “Puro e disposto a salire a le stelle“, “L’amor che move il sole e l’altre stelle“: at the end of each of the three cantiche shaping the “Divina Commedia”, Dante reminds us that the act of contemplating the stars is associated with a state of personal fulfilment to which man instinctively, albeit with difficulty, tends. “Save the dark” and “protect the night” are becoming human’s next mantras in their fight for survival.