[English version below]

[English version below]

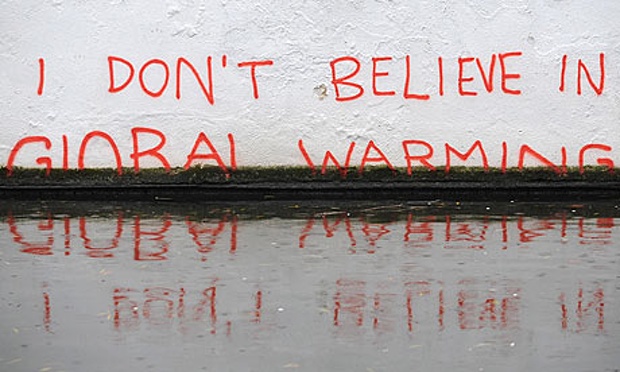

Il cambiamento climatico è la notizia più grande mai esistita nel mondo del giornalismo, eppure il giornalismo non è mai riuscito a raccontarla. Il cambiamento climatico è, allo stesso tempo, la maggiore minaccia all’umanità.

È per questo che il caporedattore del Guardian, Alan Rusbridger, ha deciso di invertire la tendenza sfidando i limiti del giornalismo – e il come la notizia più grande mai esistita veniva narrata.

Proprio la campagna del Guardian è fra i finalisti del Premio AICA 2014, nella categoria “Comunicare il Protocollo di Kyoto”; scelto per l’impegno e l’innovazione nel comunicare il cambiamento climatico, il quotidiano inglese ha iniziato a coprire la tematica usando una nuova narrativa. Il tema è più caldo che mai, in quanto combina scienza, politica, economia e finanza, filosofia. Insomma, l’umanità.

Uno dei motivi per il cambiamento climatico non fa notizia è quello della velocità alla quale esso avviene, non giornalistica: troppo lento, nel suo inesorabile procedere, per l’orologio della stampa; non cattura l’attenzione dei lettori, non è notizia “vendibile” dai giornalisti, se non in occasione di qualche (ormai non più) raro episodio sensazionale di disastro naturale, che comunque dura pochi giorni. L’attenzione cala immediatamente dopo, solo per risvegliarsi alla catastrofe successiva. Quando il pericolo non sembra imminente, è difficile catalizzare l’attenzione del pubblico su un insieme di eventi percepiti troppo lontani nel futuro.

Nei suoi ultimi sei mesi al Guardian, Alan Rusbridger si è inventato un nuovo modo di comunicare il cambiamento climatico, potente e mirato: innanzitutto, il tema è finito sulla home page del quotidiano almeno tutti i venerdì – già questo aspetto si caratterizza come una innovazione epocale; la base della campagna resta quella di investigazioni, analisi e reportage, ma si è unita a video e foto emozionanti, alla mappatura di potenti lobby – alle quali, con la petizione Keep it in the ground , viene chiesto di smettere di investire nei carburanti fossili. Serviva, però, ancora un nuovo modo di comunicare il cambiamento climatico, un nuovo taglio: ecco l’idea di una serie di podcast settimanali, “The biggest story in the world”; episodi che raccontano come la serie si è sviluppata e come sono stati condotti i reportage, facendoci entrare dietro le quinte della redazione, ascoltare le sue riflessioni, testimoni anche degli errori. Questi podcast sono forse unici nel loro genere: analizzano infatti i diversi angoli sotto i quali osservare la crisi climatica, dalla psicologia alla base del disinteresse verso l’argomento fino alle complesse implicazioni economiche.

Tutto ciò ha contribuito a generare un traffico di 4 milioni di utenti singoli al mese che leggevano articoli e dossier sul tema del cambiamento climatico.

Come reagiscono i lettori? Come ci lascia tutto questo? Il Guardian spera che non ci lasci impotenti e impauriti, ma che la campagna ispiri a dare il proprio contributo concreto, agendo nel nostro ambiente. Ma prima ancora, informandosi; perché si tratta davvero della maggiore minaccia alla Terra, e dunque, di un problema dai contorni esistenziali.

A new way to tell “The biggest story in the world”

“Climate change is the biggest story journalism has never successfully told”. Yet, it is “the greatest threat to humanity”.

That is why The Guardian’s editor-in-chief, Alan Rusbridger, has decided to challenge the established journalistic communication – and the way the story was told.

The Guardian’s campaign is among the finalists of the AICA Award 2014 in the category “Communicating the Kyoto Protocol”; chosen for its commitment and innovation in communicating climate change, the British newspaper has started to cover the issue using a new narrative. The topic is hot, as it combines science, politics, economics and finance, philosophy. In a word, humanity.

One reason why climate change rarely makes it to the top news is the pace at which it happens: changes are too slow, albeit inexorable, to gain the attention of the news and media industry; nor it does captures readers, except when those (not anymore) rare sensational episodes of natural disasters happens, the coverage of which, however, lasts few days. The red flag waves for some time, but the attention on the issue inevitably loses focus and strength. Until the next catastrophe. When the danger does not seems imminent, it is quite hard to attract readers on a set of events perceived as too far in the future.

During the last six months he had left editing The Guardian, Alan Rusbridger figured out something powerful and focused: climate change gained the home page on Fridays – and this is already unprecedented; the basis of the campaign remained investigations, analysis and reports, but the newspaper added exciting photos and videos, mapping powerful lobbies – which, with the petition Keep it in the ground, were urged to stop investments in fossil fuels by literally keeping them in the ground. But a new way of communicating climate change, a new angle was still needed: here the idea of ??a series of weekly podcasts, “The biggest story in the world”; episodes telling the world how the series itself has evolved and how reports were conducted, allowing us behind the scenes with the editors team, listen in their reflections, witnesses of their mistakes. These podcasts are probably unique as they analyze the climate crisis through several angles: from the psychology element underlying the lack of public interest, to the complex economic implications. All this has helped creating a traffic of 4 million unique visitors per month browsing on the Guardian’s climate change coverage.

How does this leave us? How do readers react? The Guardian hopes it do not leave us helpless and frightened, but instead that the campaign inspires to give a concrete contribution, starting with taking action around us, in our environment. But before that, acting by being informed; because this is the biggest threat to the Earth, and therefore, a problem facing our own existence as human beings.

Giulia Basilici